“A Mama by Your Side” – How Blind People Run a Marathon

29th Oktober 2021

When blind people run, they are never alone. “Without a guide, we would be lost,” says world-class blind runner Henry Wanyoike. With his longtime coach, Paul, the para-athlete manages to communicate perfectly while running. Connected by a thin string, the two compete in the world’s biggest marathons. But how can blind people find their way among all the other runners? The answer lies in the rhythm.

Content:

Blind runners and their guides – they need the same rhythm

“If he pulls, I run to the right” – how blind people communicate while running

When staying hydrated is the biggest challenge

Henry Wanyoike is an exceptional athlete: a multiple world record holder, gold medal winner and sought-after runner in his home country. No wonder, after all, he made Kenyan history in 2000 when he won the 5,000-meter race in Sydney at his Paralympic debut. In para-athletics, this was a sensation. At the time, he pulled the guide, who was actually supposed to lead him, the last few meters across the finish line. While Henry threw his arms up in the air after his victory and danced on the tartan track, his guide collapsed. But how was that even possible?

“The guide is like a mom taking care of her baby,” says Henry Wanyoike. When blind people run, they can’t do it alone. They have running companions, so-called guides, close by their side. Together, the two form a running tandem. However, it takes time – sometimes several years – to find the perfect running tandem of a blind runners and a guide. This is the case with Henry Wanyoike.

Blind runners and their guides – they need the same rhythm

In 2005, the Kenyan set his personal best marathon time. In Hamburg, he ran 2:31:31 hours at the time. Wanyoike was suddenly the fastest blind runner in the world – and got himself into trouble.

The problem is that only very few people are capable of running a marathon in two and a half hours while leading a blind person. Henry Wanyoike knew how to help himself. Instead of having one guide, he relied on several partners. He changed his running companion every 12 to 15 kilometers during a marathon – until he met Paul.

PERFECT FOR ANY PACE SHARPENING:

DISCOVER THE U-TECH SOLO

RUNNING FAST AND ENJOYING TO FLY

Midfoot, forefoot, or rearfoot strikers – all runners who want to step on the gas have one thing in common: they touch the ground farther at the front of the sole. This is exactly where we placed a new version of our unique U-TECHTM technology, Double U. Inspired by the natural motion you sink into the twofold U-shaped construction. U-TECHTM surrounds your foot, centers forces, and thus provides you with support and physiological stability.

Henry met Paul in his hometown in Kenya. There, Paul trained a running group in which Henry also ran every now and then. “Henry is not only a friend to me, but almost a brother,” says Paul Wanyoike. Even though they share the same last name, the two runners are not related. Paul, however, knows what he has gotten himself into as a guide.

“As a guide, I am the one who can help a friend achieve their goals”

When a blind runner wins a race, he or she is the first to be in the spotlight. For a long time, this was also the case in para-athletics competitions. In the meantime, this has changed. Today, the accompanying runners also win medals and trophies.

“The attention for blind runners is increasing – that goes for us guides, too,” Paul says. That’s nice and much appreciated, he says. But for guides, it’s just not everything. “As a guide, I feel more like I’m the one who can help a friend reach their goals,” Paul says, adding, “plus, we benefit a little bit ourselves, running the biggest marathons in the world and keeping fit.” He laughs.

It is obvious that the two are a good match for each other. Their track times prove it – even though Paul is more than a whole head taller than Henry. “Of course, it took us a little while to get used to each other,” Henry admits. A blind runner must certainly have a certain amount of basic trust in his guide. But it’s “not really about trust per se,” the world-class runner explains. “When someone decides to become a guide for a blind runner, they have to know that they’re doing it primarily for the other person.” That’s crucial, he says.

Like most professional guides, Paul knows this too. His size would enable him to take different, much longer strides than Henry. But the two have created a choreography of the way they run together. “It’s all about rhythm,” Henry says. “That is really incredibly important. Especially the rhythm of our hands.”

“If he pulls, I run to the right” – how blind people communicate while running

Blind runners have to rely on their head and their intuition. “For me, running is not only a workout for my body, but above all a workout for my head,” says Henry Wanyoike. Sometimes after a marathon, he says, his head is more tired than his legs. “The challenge for me in running is to be highly focused the whole time.” That sounds surprising at first, but it shows how challenging running can be for blind people.

Unlike sighted people, blind runners cannot detect obstacles, turns, hills, or slopes hundreds of meters in advance. For them, their guides are their eyes at such moments. “Paul and I communicate constantly, almost all the time,” Henry explains, “without really talking much.”

A small string, similar to a shoelace, connects the two runners. This is quite normal in blind runs. If blind people and their guides run together frequently, they perfect their coordination – like Henry and Paul. “When Paul’s not talking to me, he can guide me with the string,” Henry says. “If he pulls it, I run to the right.” If Paul pushes Henry away from him with his elbow, Henry knows to run to the left. If the guide raises his hand, blind runners know to lift their leg.

At the start, guides take their runners by the hand

The string is like an umbilical cord, says Henry. Sometimes, however, it has to be cut. Blind runners often run with their guides in regular competitions. Henry, too, usually starts alongside people who can see. But that’s a problem, especially at the start.

“Most of the time, only the people next to us realize that we are a running tandem,” says Henry. However, the first few kilometers of a marathon are particularly chaotic. If you’re not careful, you’ll get run over – or run into the heels of others. “This is great stress for Henry, but also for me,” says running companion Paul. “I have to keep an eye on everything; not only on what’s happening around me, but also around Henry."

The two have learned from this. Like many other running tandems, Henry and Paul start at the far edge of competitions. That’s where the friction is lowest and the chances for sidestepping are best. Instead of the string, Paul then grabs Henry’s hand. “The chaos at the start unsettles me,” Henry admits. The danger of falling down is great. Holding his hand, Paul has more control over his running partner.

For about two to three kilometers at the start, the two run hand in hand instead of with the string. Then the turmoil has subsided. “The start is certainly an obstacle,” Henry says. “For that reason alone, our times are not comparable to what sighted people can run.”

When staying hydrated is the biggest challenge

However, blind runners lose time not only at the start. Drinking in particular costs valuable seconds – and causes stress for blind runners and guides alike. “Drinking while running is not so easy if you are blind,” says Henry, smiling. “When one of us is thirsty, we let the other know.” Paul then gets Henry ready to grab a drink.

When the two reach a water stand, Paul, as a guide, slows the pace. He focuses on grabbing a water for himself and a water for Henry at the same time. As soon as Paul has the cups in his hand, he gives Henry a signal – and puts one into his hand. That doesn’t always work, though. Every now and then, a cup falls onto the tarmac. The two then stop – and running companion Paul turns around to get another cup.

The guide studies the route

It is also thanks to Paul that Henry knows where the next water stand will be. In the past, he would have tried to memorize the route during the walk a few days before the start. Today, he no longer does that. “As a blind runner, it didn’t do me much good,” he says.

Instead, guide Paul grabs the course map and studies problem spots. These are mainly tight turns, climbs, or descents. Together, the two then go to the briefing – especially to find out where the water stands are along the route.

“I have to have a clear head,” says Henry Wanyoike. He says he is mentally stressed by having to analyze the course before the run, but not knowing where they will get water. But once he has a clear head, Henry can enjoy the spectators at the side of the course. They give him strength, he says. Only in New York, he says, are they too loud. “Then,” Henry relates, “I lose my focus. And I no longer know which direction I’m running in.”

NEVER RUN OUT OF

NEWS

Discover all True Motion stories – and be the first to hear about new products, promotions and events. Simply, center your run!

NEVER RUN OUT OF

NEWS

Discover all True Motion stories – and be the first to hear about new products, promotions and events. Simply, center your run!

READ THE NEWEST

U-RUN STORIES

Sabrina Mockenhaupt: This shoe got me running again

2025-10-31

Sabrina Mockenhaupt has achieved everything that many runners dream of. Running was and is her life, until the pain eventually became too much. Today, she is running pain-free again – this is her story.

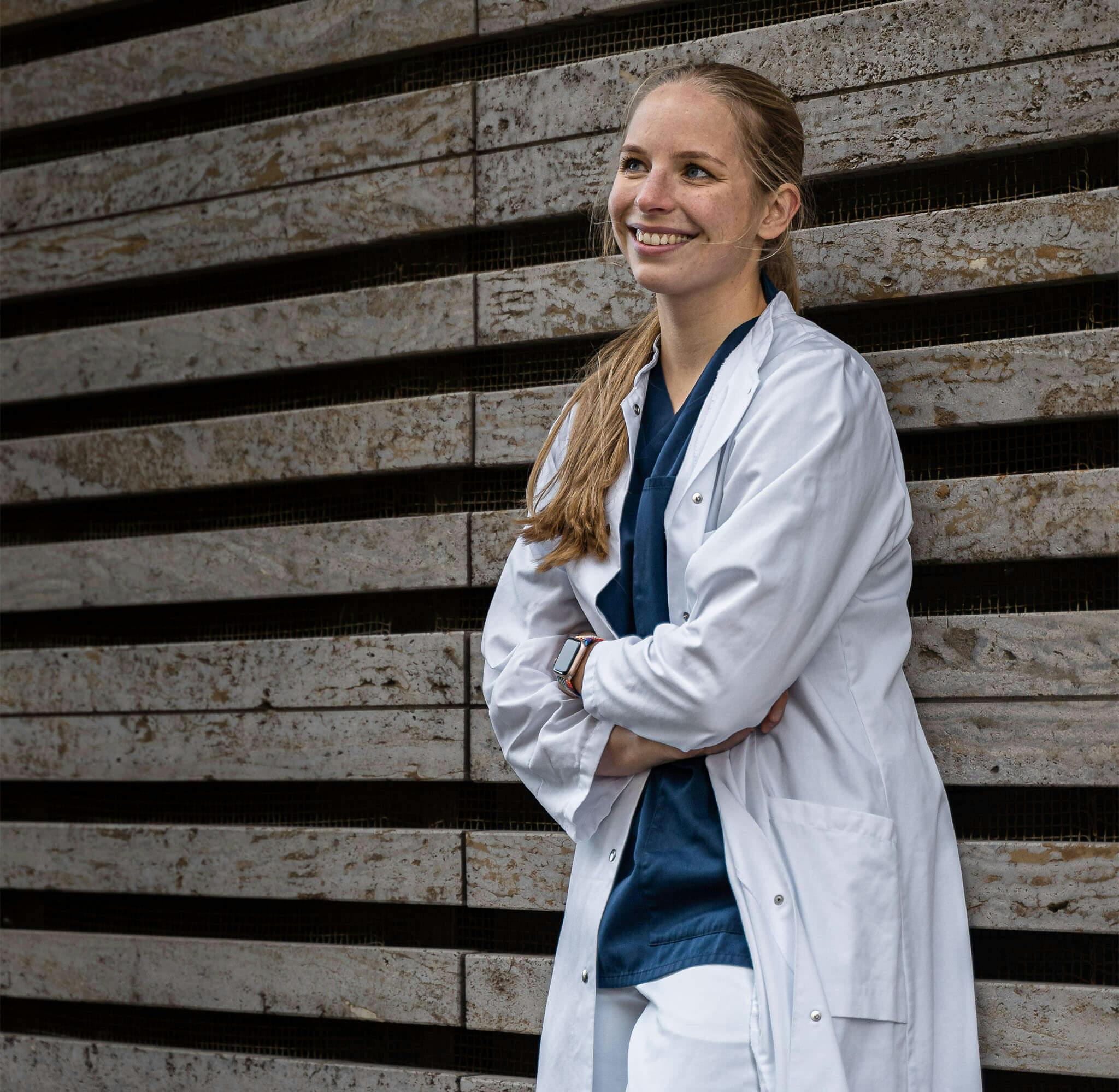

Laura Schmidt: I have rediscovered running for myself

2025-03-07

My name is Laura. I started running eight years ago – to clear my head after work. But knee pain kept me from being able to run regularly. A new pair of running shoes was finally the solution. Today I run pain-free. This is my true runner story.

READ THE NEWEST

U-RUN STORIES

Sabrina Mockenhaupt: This shoe got me running again

2025-10-31

Sabrina Mockenhaupt has achieved everything that many runners dream of. Running was and is her life, until the pain eventually became too much. Today, she is running pain-free again – this is her story.

Laura Schmidt: I have rediscovered running for myself

2025-03-07

My name is Laura. I started running eight years ago – to clear my head after work. But knee pain kept me from being able to run regularly. A new pair of running shoes was finally the solution. Today I run pain-free. This is my true runner story.

RECOMMENDED BY

RECOMMENDED BY

GET 10 % OFF YOUR FIRST ORDER!

Get your personal running updates with exclusive discounts, product news, training plans and tips for healthy running - straight to your inbox. 10% discount on your next order.

SERVICE

ABOUT US

© 2025 True Motion Running GmbH